The Best and Worst GCC Compiler Flags For Embedded

Compilers have hundreds of flags and configuration settings which can be toggled to control performance optimizations, code size, error checks and diagnostic information emitted. Often these settings wind up being copy and pasted from project to project, makefile to makefile, but it’s good to periodically audit the current options selected for a project.

In this article we will explore some of the best and worst compiler flags for GCC (and Clang). Our focus will be on flags used for embedded projects but the reasoning applies to other development environments as well. We will explore the impact each flag has by walking through practical C code examples.

Table of Contents

Context

For any embedded software project, three aspects typically crucial for success are:

- Catching common programmatic errors before executing any code

- Generating a binary that is debuggable

- Minimizing code size and RAM usage

The flags presented in this article were chosen based on how much they have aided or hindered working towards these goals on projects I’ve been involved with.

Compiling Example Code

If you would like to follow along compiling the examples presented in this article, all the

code can be found on Github1. To compile the examples, you will need the 8.3.1 GNU Arm Embedded2

toolchain and make installed on your computer.

The Best Aggregate Warning Options

Compiler warnings are the first line of defense against catching various errors that could arise at runtime and enforcing conventions that lead to a more readable codebase. It is a lot easier to fix issues at compilation time than when unexpected behavior is encountered on your platform.

GCC and Clang have several warning flags which will enable a collection of useful checks which we will explore in more detail below.

NOTE: When enabling warning flags for a project that hasn’t used them previously, there will likely be a ton of warnings. I’d recommend taking an incremental approach when transitioning the project by only compiling parts of your system (i.e new files) with a more stringent set of warning flags or enabling and fixing sets of warnings at a time. Trying to fix thousands of warnings all at the same time is a recipe for introducing regressions or upsetting fellow developers trying to review your change.

-Wall & -Wextra

The compiler flag -Wall enables a base set of warnings generally agreed upon as being useful and easy to fix. -Wextra enables an additional set of flags not covered by -Wall

The exact list of flags varies between compiler versions but can easily be found by consulting the GCC documentation for the compiler version you are using3.

Here’s a c snippet that will happily compile but has a couple unfortunate bugs.

static void prv_various_memset_bugs(void) {

#define NUM_ITEMS 10

uint32_t buf[NUM_ITEMS];

memset(buf, NUM_ITEMS, 0x0);

memset(buf, 0x0, NUM_ITEMS);

}

The issues can easily be caught at compile time by using the -Wall flag.

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-Wall make

main.c: In function 'prv_various_memset_bugs':

main.c:19:3: warning: 'memset' used with constant zero length parameter; this could be due to transposed parameters [-Wmemset-transposed-args]

memset(buf, NUM_ITEMS, 0x0);

^~~~~~

main.c:20:3: warning: 'memset' used with length equal to number of elements without multiplication by element size [-Wmemset-elt-size]

memset(buf, 0x0, NUM_ITEMS);

-Werror

-Werror causes all enabled warnings to cause compilation errors. This can be incredibly

useful to ensure that no new warnings slip into a codebase. When working with a team,

not everyone may be as excited about fixing compiler warnings as you. I really consider this flag a

must have to prevent code with warnings from being merged to master.

Enabling -Werror does mean that when the compiler version changes, new compilation errors may

appear (since new sets of warnings are usually added to flags like -Wall and pre-existing checks

are improved and can catch new errors). Typically, it’s a very small set of changes required to fix

the new issues detected.

NOTE: I’d recommend enforcing a certain compiler version be used in your build system (for local development and in CI). That way everyone will see the exact same errors and behavior. As new versions become available, one team member can update to the new version, fix up any new issues, and then merge an update requiring that compiler version be used by the rest of the team.

Sometimes, there may be warnings you do not wish to trigger an error or even a warning. These can easily be controlled with the following compiler options:

-

-Wno-<warning>to disable the warning altogether -

-Wno-error=<warning>to keep the warning enabled but not trigger an error.

Let’s try it out for our example above! For example:

# Warn about memset-elt-size but don't error on it

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wall -Werror -Wno-error=memset-elt-size" make

main.c: In function 'prv_various_memset_bugs':

main.c:47:3: error: 'memset' used with constant zero length parameter; this could be due to transposed parameters [-Werror=memset-transposed-args]

memset(buf, NUM_ITEMS, 0x0);

^~~~~~

main.c:48:3: warning: 'memset' used with length equal to number of elements without multiplication by element size [-Wmemset-elt-size]

memset(buf, 0x0, NUM_ITEMS);

# Don't enable any warnings for memset-elt-size

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wall -Werror -Wno-memset-elt-size" make

main.c: In function 'prv_various_memset_bugs':

main.c:47:3: error: 'memset' used with constant zero length parameter; this could be due to transposed parameters [-Werror=memset-transposed-args]

memset(buf, NUM_ITEMS, 0x0);

^~~~~~

-Weverything (Clang only)

By design, Clang generally matches the set of compiler flag options available in the GNU toolchain, but there are a few that are different.

For embedded projects, it’s useful to cross-compile the source code with Clang to surface additional issues that GCC may have missed.

One flag there are some strong opinions4 about is -Weverything which literally enables every

single warning available to Clang! Many suggest you should never flip on this flag in a

build. The strategy I prefer, followed by other projects such as CppUTest5, is to enable the

warning but liberally disable warnings from it that are not useful.

I’ve found this to be a pretty neat way to discover new warning flags built into clang, such as

-Wdocumentation, which can catch errors in comments! For example,

//! A bad docstring that clang can identify issues with using -Wdocumentation

//!

//! @param a The first value of the summation

//! @param c The second value of the summation

//!

//! @return the sum of a & b

int simple_math_get_sum(int a, int b);

$ USE_CLANG=1 EXTRA_CFLAGS=-Weverything make

[...]

./simple_math.h:6:12: warning: parameter 'c' not found in the function declaration [-Wdocumentation]

//! @param c The second value of the summation

^

./simple_math.h:6:12: note: did you mean 'b'?

//! @param c The second value of the summation

^

b

The Best One-Off Warning Options (options not covered by -Wall or -Wextra)

There’s many more warnings and checks that are not enabled by -Wall or -Wextra. In this section we

will explore some of the best ones.

-Wshadow

Shadowing variables at the very least makes code difficult to read and often can be indicative of a

bug because the code is not operating on the value the programmer expects. These can easily be

detected by using -Wshadow.

int variable_shadow_error_example2(void) {

int result = 4;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

int result = i;

// do something with result

}

return result;

}

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-Wshadow make

main.c: In function 'variable_shadow_error_example2':

main.c:55:9: warning: declaration of 'result' shadows a previous local [-Wshadow]

int result = i;

^~~~~~

main.c:52:7: note: shadowed declaration is here

int result = 4;

-Wdouble-promotion

The C types float and double are not the same! A float represents an IEEE single precision

floating point number whereas a double represents double precision floating point number. ARM

Cortex-M MCUs with a Floating Point Unit (FPU) only natively supports single precision floating

point numbers. This means when a double is used, the compiler will need to emulate the operation with a

function (instead of a native instruction). If you examine the output of code using a double, you will see functions like

__aeabi_d2f in the code.

Using a double not only affects performance since the instruction is not supported natively but

also bloats the codesize because it pulls in some not-so-small functions.

When using floating point numbers in a project, it’s quite easy to unintentionally use a double:

bool float_promotion_example(float val) {

return val > 2.6;

}

which results in a code size of:

$ arm-none-eabi-size build/examples.elf

text data bss dec hex filename

1420 4 0 1424 590 build/examples.elf

# Look at large emulated instructions pulled into project

$ arm-none-eabi-nm -S -l --size-sort build/examples.elf | grep aeabi

00008518 00000010 T __aeabi_cdcmpeq

00008518 00000010 T __aeabi_cdcmple

00008528 00000012 T __aeabi_dcmpeq

00008564 00000012 T __aeabi_dcmpge

00008578 00000012 T __aeabi_dcmpgt

00008550 00000012 T __aeabi_dcmple

0000853c 00000012 T __aeabi_dcmplt

00008388 0000001e T __aeabi_ui2d

00008508 00000020 T __aeabi_cdrcmple

000083a8 00000022 T __aeabi_i2d

000083cc 00000042 T __aeabi_f2d

00008420 0000005a T __aeabi_l2d

00008410 0000006a T __aeabi_ul2d

00008110 00000276 T __aeabi_dadd

0000810c 0000027a T __aeabi_dsub

The reason a double gets used above is because according to the C standard a floating point

constant, i.e 2.6, will be of a double type. To use a float, the constant must be declared

as 2.6f.

Fortunately, a warning can be enabled to easily catch when this implicit double promotion takes place:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wdouble-promotion -Werror" make

float_promotion.c: In function 'float_promotion_example':

float_promotion.c:4:14: error: implicit conversion from 'float' to 'double' to match other operand of binary expression [-Werror=double-promotion]

return val > 2.6;

Let’s fix the issue by replacing 2.6 with 2.6f and recompile:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wdouble-promotion -Werror" make && arm-none-eabi-size build/examples.elf

text data bss dec hex filename

244 4 0 248 f8 build/examples.elf

$ arm-none-eabi-nm -S -l --size-sort build/examples.elf | grep aeabi

We see all the compiler (__aeabi_*) functions are gone and we have saved nearly 1200 bytes of codespace!

-Wformat=2 & -Wformat-truncation

By default, -Wall enables -Wformat which turns on a variety of checks to make sure any formatter

strings used in standard library routines (i.e printf, sprintf, etc) are valid. However,

there’s a bunch of extra formatter checks that can only be enabled individually6.

One interesting option is upgrading the -Wformat check level to 2 which includes a couple additional

checks such as -Wformat-security. Let’s take a look at an example where a string to print is

passed but no sanitization on the string is performed.

void print_user_provided_buffer(char *buf) {

printf(buf);

}

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wformat" make

# No issues identified

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wformat=2" make

main.c: In function 'print_user_provided_buffer':

main.c:78:3: warning: format not a string literal and no format arguments [-Wformat-security]

printf(buf);

NOTE: A pretty slick feature with GCC is being able to enable format checks for custom functions7. This is accomplished using the format attribute:

int my_printf (void *a, const char *fmt, ...) __attribute__ ((format (printf, 2, 3)));

Another interesting set of formatter warning flags not enabled by default is -Wformat-overflow and

-Wformat-truncation. The options are able to detect various types of buffer overflows and

truncation that could arise when using routines such as sprintf and snprintf respectively:

void snprintf_truncation_example(int val) {

char buf[4];

snprintf(buf, sizeof(buf), "%d", val);

}

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wformat-truncation=2" make

main.c: In function 'snprintf_truncation_example':

main.c:87:31: warning: '%d' directive output may be truncated writing between 1 and 11 bytes into a region of size 4 [-Wformat-truncation=]

snprintf(buf, sizeof(buf), "%d", val);

^~

main.c:87:3: note: 'snprintf' output between 2 and 12 bytes into a destination of size 4

snprintf(buf, sizeof(buf), "%d", val);

-Wundef

A classic bug encountered in C code is an undefined macro silently evaluating as 0 and causing

unexpected behavior. For example, consider a define used in a codebase, ACCEL_ENABLED, which controls whether or not the accelerometer code responsible for step tracking is initialized.

There are several bugs that can pretty easily go unnoticed:

- A file references

ACCEL_ENABLEDbut doesn’t pick up the appropriate configuration header where the macro is defined so the accelerometer related code in the file gets compiled out. - The correct configuration header is sourced but a programmer mistypes the name of the macro (i.e

ACCEL_ENABLEinstead ofACCEL_ENABLED) and so the code also gets compiled out.

These classes of errors can easily be identified by using the -Wundef flag:

#if ACCEL_ENABLED

//

// accelerometer configuration code

//

#endif /* ACCEL_ENABLED */

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-Wundef make

main.c:13:5: warning: "ACCEL_ENABLED" is not defined, evaluates to 0 [-Wundef]

#if ACCEL_ENABLED

Note that this type of check is not possible when the check is preceded by the ifdef (anti-)pattern check:

#if defined(ACCEL_ENABLED) && ACCEL_ENABLE

// typo "ACCEL_ENABLE" (instead of ACCEL_ENABLED) will go unnoticed

#endif

In general, it’s advisable to use #ifdef sparingly in a project for these reasons.

-fno-common

Ideally a codebase doesn’t use many global variable declarations but I’ve seen so many libraries that do.

Consider the following situation where we have two c files which reference the same variable name but intend to use the variable individually:

//

// File main.c - g_variable defined for later use in the file

int g_variable = 4;

//

// File tentative_global.c

//

int g_variable;

void tentative_global_init(int initial_value) {

g_variable = initial_value;

}

int tentative_global_increment(void) {

g_variable++;

}

The confusing part here is that the snippet above will compile without any duplicate symbol

warning. This is because int g_variable without an initializer is a tentative definition. A

tentative definition does not initially allocate any space for the variable and at link time will

either be resolved to a pre-existing symbol if a symbol of the same name already exists or

otherwise space will be allocated.

This can lead to some confusing side effects if the programmer thinks unique instances of the variable are being operated on within each c file.

A neat way to catch this kind of issue is to compile with -fno-common which disables the ability

for tentative definitions to be merged into a pre-existing definition. This will lead to a

duplicate symbol warning being emitted at link time:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-fno-common make

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: <path_to_file1.o>:(.bss+0x0): multiple definition of `g_variable'; <path_to_file2.o>:(.data+0x0): first defined here

-fstack-usage & -Wstack-usage=

For embedded development, there is often not a lot of RAM available to allocate for stack space (typically on the order of a few hundred to a few thousand bytes). Therefore, stack overflows can be very common especially if the programmer is not careful about what local variables they put on the stack.

There’s a useful pair of flags which can be used to monitor stack space in a function and emit warnings when the usage is too high.

To generate stack depth information, you need to use the -fstack-usage flag which will emit .su

files for each c file you compile. Tools like Puncover8 will even analyze the stack space

information emitted and generate maximal stack depth estimations based on call path.

Let’s compile the following and inspect the .su file which is output:

#include <stdint.h>

int stack_usage_example(int num) {

uint8_t tmp[256];

[... operations on tmp ...]

}

int vla_stack_usage(int num) {

if (num <= 0) {

return -1;

}

uint8_t tmp[num];

[... operations on tmp ...]

}

The .su file will look like:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-fstack-usage make

$ cat stack_usage.su

stack_usage.c:3:5:stack_usage_example 256 static

stack_usage.c:14:5:vla_stack_usage 16 dynamic

We will see the stack usage of the function in bytes followed by static if the usage is fixed or dynamic if the

entire stack usage cannot be computed at compilation time because a variable length array (VLA) was

used.

-Wstack-usage=<stack_limit> can also be leveraged to emit a warning when stack usage exceeds a

certain value. Let’s try it out!

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=" -Wstack-usage=255" make

stack_usage.c: In function 'stack_usage_example':

stack_usage.c:3:5: warning: stack usage is 256 bytes [-Wstack-usage=]

int stack_usage_example(int num) {

^~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

stack_usage.c: In function 'vla_stack_usage':

stack_usage.c:14:5: warning: stack usage might be unbounded [-Wstack-usage=]

int vla_stack_usage(int num) {

-Wconversion

When arithmetic operations are performed on integer types (i.e uint8_t, int8_t, uint16_t,

etc) a set of implicit conversions on the types can take place. First integer promotion

occurs. The C standard defines this as9:

If an int can represent all values of the original type (as restricted by the width, for a bit-field), the value is converted to an int; otherwise, it is converted to an unsigned int.

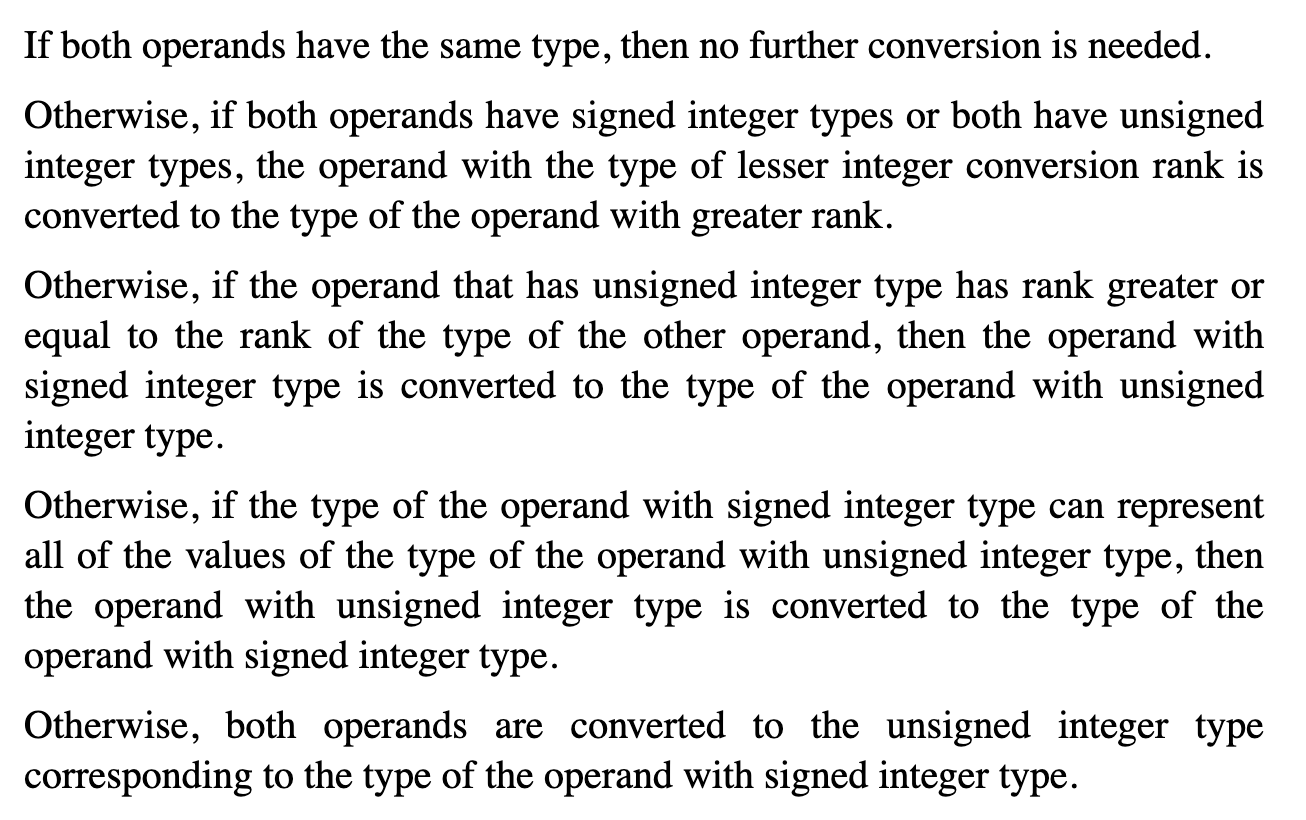

Then the following set of rules are applied to the promoted values:

It can be hard to keep track of the set of conversions taking place but fortunately the

-Wconversion option can be used to generate warnings when implicit conversions that are

likely to change the underlying value take place. This warning can be tedious to eliminate from a codebase

but I’ve seen it help catch real bugs on numerous occassions in the past.

Consider the following simple example as an illustration:

uint8_t conversion_error_example(uint32_t val1, uint8_t val2) {

uint8_t step1 = val1 * val2;

int final_step = step1 / val2;

return final_step;

}

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-Wconversion -Werror" make

main.c: In function 'conversion_error_example':

main.c:91:19: error: conversion from 'long unsigned int' to 'uint8_t' {aka 'unsigned char'} may change value [-Werror=conversion]

uint8_t step1 = val1 * val2;

^~~~

main.c:94:10: error: conversion from 'int' to 'uint8_t' {aka 'unsigned char'} may change value [-Werror=conversion]

return final_step;

The Best Options for Debugability & Code Size

-g3

When a binary is loaded on an embedded device, it is important that debug information is included in the ELF. Otherwise, gdb (or your IDE) will not be able to display variables or backtraces. There are many “Debug Option” flags10 one can use to control the diagnostic information emitted.

Typically you will see a project use -g but consider compiling with -g3. It will include

a couple extra goodies such as macro definitions used in your application which can be useful to be

able to print in gdb especially when the definition comes from a chain of definitions.

You can try it out by compiling:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-g" make

$ arm-none-eabi-readelf --debug-dump=macro build/examples.elf | grep MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO

(gdb) p/x MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO

No symbol "MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO" in current context.

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-g3" make

$ arm-none-eabi-readelf --debug-dump=macro build/examples.elf | grep MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO

DW_MACRO_define_strp - lineno : 13 macro : MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO 0x4d

(gdb) p/x MEMFAULT_EXAMPLE_MACRO

$1 = 0x4d

-Os

You can find all the details about optimization flags in the “Optimization Options” section of the

GNU GCC docs11. -Os, optimize for size, is generally the optimization flag you will see used

for embedded systems. It enables a good balance of flags which optimize for size as well as

speed. Forgetting to flip on this flag can have serious code size impacts. For more details check

out the interrupt series of posts about it!

-ffunction-sections, -fdata-sections, & --gc-sections

Clearly a favorite of ours as we’ve touched upon these flags in several articles12 13 but worth mentioning again. I’ve seen a surprising number of embedded projects over the years that forgot to enable these flags for portions of the project.

By default the linker will place all functions in an object within the same linker “section”. This

becomes very clear when examining the mapfile and seeing a bunch of symbols in the .text section.

.text 0x0000000000008238 0x60 /var/folders/dm/b0yt_1d11z9d53rtsm3y74sm0000gn/T//ccqZLzPH.o

0x0000000000008238 simple_math_get_sum

0x0000000000008268 simple_math_get_delta

With -ffunction-sections, each function gets its own section:

.text.simple_math_get_sum

0x0000000000008238 0x30 /var/folders/dm/b0yt_1d11z9d53rtsm3y74sm0000gn/T//ccC7FiQW.o

0x0000000000008238 simple_math_get_sum

.text.simple_math_get_delta

0x0000000000008268 0x30 /var/folders/dm/b0yt_1d11z9d53rtsm3y74sm0000gn/T//ccC7FiQW.o

0x0000000000008268 simple_math_get_delta

As the linker resolves references between objects it will mark a section as used. A final optimization pass it can make is to cull any unused sections. For larger projects, this will often result in substantial code savings.

This optimization is enabled by passing --gc-sections to the linker. Diagnostic logs about the

sections dropped can also be displayed using --print-gc-sections linker option. Let’s try it out:

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS="-ffunction-sections -fdata-sections" EXTRA_LDFLAGS="--gc-sections --print-gc-sections" make

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.variable_shadow_error_example2' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.flash_read' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.print_user_provided_buffer' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.printf' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.simple_math_get_delta' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.stack_usage_example' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.text.vla_stack_usage' in file '<path_to_file>'

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: removing unused section '.comment' in file '<path_to_file>'

-Wpadded

Warn if padding is added to a structure due to alignment requirements:

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdint.h>

// Note: clang will only warn in the below examples if there's an instance of a

// structure definition with a padding violation

// The below 'struct padded' causes this warning:

// <source>:8:1: warning: padding struct size to alignment boundary [-Wpadded]

// 8 | };

// | ^

struct padded {

uint16_t a;

uint8_t b;

} padded;

// The below 'struct aligned' causes this warning:

// <source>:14:14: warning: padding struct to align 'a' [-Wpadded]

// 14 | uint16_t a;

// | ^

struct aligned {

uint8_t b;

uint16_t a;

} aligned;

// The same struct, but force packed- no warning is emitted because no padding

// is added. Note that this can have negative effects on code generated to

// access struct members; this should really only be used for structures that

// need to be consistently laid out for external interfaces (eg a SPI flash

// command data packet)

struct __attribute__((packed)) packed_aligned {

uint8_t b;

uint16_t a;

} packed_aligned;

// This structure is aligned to field widths, and there's some manual padding at

// the end to fill unused space; since all memory in the structure has a type

// associated with it, an added benefit is C initializer rules will allow us to

// safely use eg 'memcmp' when comparing (initialized) instances of the

// structure. See https://godbolt.org/z/5Wdhdx for an example of how this can

// fail otherwise!

struct naturally_aligned {

uint32_t a;

uint16_t b;

uint8_t c;

uint8_t _pad[1];

};

// memcmp(&one, &two, sizeof(one)) == 0

struct naturally_aligned one = {0}, two = {0};

// Confirm all the fields in 'struct naturally_aligned' are where we think they

// should be, and the total structure size matches expectation

_Static_assert(offsetof(struct naturally_aligned, a) == 0, "ok");

_Static_assert(offsetof(struct naturally_aligned, b) == 4, "ok");

_Static_assert(offsetof(struct naturally_aligned, c) == 6, "ok");

_Static_assert(sizeof(struct naturally_aligned) == 8, "ok");

This warning is helpful if you want to optimize the structure definitions in your program (could be considered in a last-stakes optimization effort, or if you’re interested in really polishing those structure definitions). It can be quite an exuberant warning in existing codebases.

The pahole utility can be used on an existing elf to scan for padded struct definitions, or if you really wanted to, as part of a CI step banning unoptimized structure definitions 😅 though the compiler flag should be enough.

I’d be remiss if I left out a reference to this legendary article, “The Lost Art of Structure Packing”

The Worst

In the following subsections we will explore some of the “worst” flags available for embedded devices that can result in hard to triage issues and subtle bugs.

-fshort-enum

A really unfortunate flag that is hard to avoid is -fshort-enum. This flag allows the compiler to change the type of an enum based on the declared range of values. For example,

enum StatusCode {

kStatusCode_Success = 0,

kStatusCode_Failure = 0xff,

}

would be stored in a single byte type such as a uint8_t since the range is from 0 to 255 and

enum StatusCode {

kStatusCode_Success = 0,

kStatusCode_Failure = 0xffffffff,

}

would be stored in a four byte type such as a uint32_t since the range is from 0 to UINT32_MAX.

Some of the blame here is on the C specification & ARM ABI itself which supports two modes for representing enums. Section “7.1.3 Enumerated Types” of the ARM Procedure Call Standard documentation14 states that the two permitted ABI variants for enumeration types are:

- An enumerated type normally occupies a word (int or unsigned int). If a word cannot represent all of its enumerated values the type occupies a double word (long long or unsigned long long).

- The type of the storage container for an enumerated type is the smallest integer type that can contain all of its enumerated values

There a few key disadvantges of truncating enums to the shortest width type:

- Binary compatiblity can be broken if the values in an enum change between releases. For example, if the max value in one version is 255 and then in a future version it’s 4096, the size of the enum will change from a 1-byte to a 2-byte representation. This means linking against a pre-compiled library using the older version of the enum will no longer work.

- When operations are performed on sizes that don’t match the size of the architecture, extra instructions are often needed to mask out bits in the register, which uses more code space. This can easily be seen with the for loop example below.

- Enum types can wind up in packed structures. Changing the legal values of an enum can then cause unexpected breakages because the size of the enum member and consequently the structure will change. If an enum is used in a struct saved on flash, for example, after a firmware update the code may no longer be able to read the data from flash correctly.

Comparison of for loop using uint8_t and int

The following is an example of how operating on a shorter width type (uint8_t) requires an extra

masking instruction than operating on a type aligned with the architecture register size

(int). When an enum is trucated to a smaller width, the same type of masking instructions may be

needed when operations are performed with it.

//! 0000807c <simple_for_loop_with_byte>:

//! 807c: 2300 movs r3, #0

//! 807e: 461a mov r2, r3

//! 8080: b2d9 uxtb r1, r3

//! 8082: 4288 cmp r0, r1

//! 8084: d801 bhi.n 808a <simple_for_loop_with_byte+0xe>

//! -- Extra instruction for masking so register holds a uint8_t

//! 8086: b2d0 uxtb r0, r2

//! 8088: 4770 bx lr

//! 808a: 441a add r2, r3

//! 808c: 3301 adds r3, #1

//! 808e: e7f7 b.n 8080 <simple_for_loop_with_byte+0x4>

//! Total function size: 20 bytes (10 instructions)

uint8_t simple_for_loop_with_byte(uint8_t max_value) {

int sum = 0;

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < max_value; i++) {

sum += i;

}

return sum;

}

//! 00008090 <simple_for_loop_with_word>:

//! 8090: 2300 movs r3, #0

//! 8092: 461a mov r2, r3

//! 8094: 4298 cmp r0, r3

//! 8096: dc01 bgt.n 809c <simple_for_loop_with_word+0xc>

//! 8098: 4610 mov r0, r2

//! 809a: 4770 bx lr

//! 809c: 441a add r2, r3

//! 809e: 3301 adds r3, #1

//! 80a0: e7f8 b.n 8094 <simple_for_loop_with_word+0x4>

//! Total function size: 18 bytes (9 instructions)

int simple_for_loop_with_word(uint8_t max_value) {

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < max_value; i++) {

sum += i;

}

return sum;

}

What to do?

The arm toolchain by default is compiled with -fshort-enum so if you are using standard

libraries (such as newlib libc). You can disable short enums by setting the -fno-short-enum flag

but if you try to link against a unit that enables short enums (such as newlib) you will see the

following linker warning:

arm-none-eabi/bin/ld: warning: <path_to_file> uses 32-bit enums yet the output is to use variable-size enums; use of enum values across objects may fail

When compiling with -nostdlib and linking your own libc implementation, it’s worth

considering compiling with -fno-short-enum so all your enums are a fixed width and cannot change

over time.

Due to the nuances of enums in C, never use enums directly in packed structures. Instead use a type with a constant size and assert if the enum does not fit within the allocated size.

typedef struct __attribute__((packed)) {

uint32_t status; // for enum StatusCode

} my_packed_struct;

_Static_assert(

sizeof(enum StatusCode) <= sizeof(((0*)my_packed_struct)->status),

"enum does not fit within structure member")

-flto

LTO (link time optimization), is an optimization pass made across all compilation units, that can help reduce the overall size of a binary. While at first this sounds great (and I’ve used it extensively on several large scale embedded projects), it should be viewed as a last resort optimization if you are desperate to save codespace in an embedded project. Here’s why:

- It’s slow. If you are trying to do bringup on a new device driver or quickly run some experiments on hardware, compilation time becomes critical. Waiting minutes for a build to complete instead of seconds can be the difference to debugging an issue in a couple of minutes or a couple of hours. Since the LTO pass runs at the link phase, it will always need to run even if only one line in one c file changed.

- It’s very hard to control memory placement when using LTO. Many embedded projects operate on systems with several regions of RAM that have different properties – some regions are slower to access than others, some are non-executable, etc. For example, you may want a graphics library function to live in the fastest single-cycle access RAM since it’s called all the time but you may not care if the graphics stack initialization is in a slow RAM region since it’s only called once when the system boots. However LTO may decide to inline all of this code into the same function and then place it all in the slower region. It is extremely hard to try and prevent LTO from doing this!

- It makes your application substantially harder to debug. This is getting better in newer releases but after an LTO pass, a lot of debug information cannot be captured due to the nature of the optimization. If a chain of seven functions across several c files is only called once, LTO may chose to inline them all together. If you crash somewhere in the seventh function, the backtrace may just show one function instead of all seven.

- LTO typically causes large increases to the stack space needed. Since LTO results in aggressive cross-object inlining, a bunch of local variables from many different functions now wind up getting allocated at the same time. When you enable LTO for the first time, expect to see some stack overflows!

-fpack-struct=n

When defining structures in C, members are aligned by their size. So for example, a

uint16_t which is 2 bytes in size will always be aligned on a 2 byte boundary. This means there

is often some padding bytes inserted into the struct to achieve this alignment.

typedef struct {

uint8_t a; // at offset 0

// 1 padding byte

uint16_t b; // at offset 2

} my_struct;

Sometimes, a programmer may try to pack all structs using -fpack-struct to save a little RAM space. This is a bad idea!

While it may reduce the RAM footprint of a codebase, it will wind up generating more code

because unaligned accesses to data generally require more instructions than aligned ones. This in

turn will impact performance. It also creates a problematic situation if you link static libraries compiled with and

without the flag because then the offset of the members within the struct will be different based

on the compilation unit!

When no value, n, is specified,-fpack-struct will pack all the structures in your

code such that there are no holes. When a value n is passed to pack struct, it will only force alignment of types greater than that

size along that boundary. So in the example below if we compile with -fpack-struct, members b & c

will be aligned but if we compile with -pack-struct=4, only c will be shifted.

typedef struct {

uint8_t a;

uint16_t b;

uint64_t c;

uint32_t d;

} my_struct;

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, a) == 0,

"a not at offset 0 within struct");

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, b) == 2,

"b not at offset 2 within struct");

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, c) == 8,

"c not at offset 8 within struct");

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, d) == 16,

"d not at offset 16 within struct");

$ EXTRA_CFLAGS=-fpack-struct=4 make

main.c:30:1: error: static assertion failed: "c not at offset 8 within struct"

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, c) == 8, "c not at offset 8 within struct");

^~~~~~~~~~~~~~

main.c:31:1: error: static assertion failed: "d not at offset 16 within struct"

_Static_assert(offsetof(my_struct, d) == 16, "d not at offset 16 within struct");

^~~~~~~~~~~~~~

NOTE: Structure packing is extremely common in embedded devices. The use case is typically when some kind of data is being serialized and sent out over a transport or saved to some kind of persistent storage. This is done to save space and be portable – compilers may pad the same struct differently. For example, on a 64 bit architecture, a struct is typically padded such that it winds up 8 byte aligned whereas on a 32bit architecture structs are usually padded to be 4 byte aligned. If you are passing data between these two architectures with the same struct definition and things are unpacked, the two structures would not be equivalent! To pack individual structures, you can use the “packed” attribute. It’s still a good idea to naturally align the members within a struct when possible for minimal code size usage and performance; see above for information on struct padding!

-ffast-math

Per the documentation15, this flag “[breaks] IEEE or ISO rules/specifications for math function” in the name of faster code. It should be avoided!

-Wunused-parameter

This warning will detect when a parameter passed to a function is never used in the function. While the goal here is to detect functions with dead parameters, as you start to build abstractions, sometimes parameters simply won’t be used by all the implementations and the code ends up cluttered by the tricks you will need to mark those parameters as used:

#define MEMFAULT_UNUSED(_x) (void)(_x)

Let’s take a look at an example:

typedef void (*FlashReadDoneCallback)(void *ctx);

static void prv_spi_flash_read_cb(void *ctx) {

// nothing to do with ctx so we'll have to add a MEMFAULT_UNUSED here to prevent the warning

MEMFAULT_UNUSED(ctx);

}

int flash_read(FlashReadDoneCallback cb, void *ctx) {

// perform flash read

// [...]

// invoke callback

cb(ctx);

}

More often then not, the usage of this flag just result in an excessive amount of

(void)(variable) calls getting litered in a codebase rather than helping to catch any real issues.

Additional Resources

If you’d like to check the flags used in various compilation units in your application, as long as

you are compiling with -g, the elf will contain this information, i.e:

$ arm-none-eabi-readelf --debug-dump=info build/examples.elf | grep "DW_AT_producer"

<c> DW_AT_producer : (indirect string, offset: 0x0): GNU C17 8.3.1 20190703 (release) [gcc-8-branch revision 273027] -mthumb -mfloat-abi=hard -mfpu=fpv4-sp-d16 -mcpu=cortex-m4 -march=armv7e-m+fp -g -Os

[...]

If you enjoy staying up to date with the latest compiler options available, the GCC release notes are an excellent resource.

If you want to use the absolute latest version of GCC for ARM, Arch Linux generally has bleeding edge version of the toolchain available for install on the OS.

Closing

We hope reading this post has taught you something interesting about compiler flags and given you some ideas of items to look into.

Are there flags you wish I had also mentioned in this article? Let me know in the discussion area below!

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub